[A Labour of Love] Maya Roy

February 2019

Welcome to our February edition of A Labour of Love: 10 years of creativity, community, and care, our special series of interviews celebrating the past decade of The Public! Each month we're taking a moment to speak with someone we've had the pleasure of working with over the last ten years to reflect on how The Public has impacted them. This one's coming to you one day short of the shortest month of the year, but we swear it's worth the wait!

In this issue, we speak with Maya Roy, Chief Executive Officer at YWCA Canada and former Executive Director of Newcomer Women's Services Toronto. Over the years, we've had the pleasure of collaborating with Maya on many projects around gendered violence, migration, empowerment, and capacity building, and we look forward to another ten years of working together!

The Public: Can you tell us how you first began working with The Public?

Maya Roy: Sheila and I were asked to co-facilitate a workshop together and then we stayed in touch from there. When I moved to Newcomer Women’s Services, I was just really impressed with Shameless Magazine, and when the provincial government wanted us to do work around forced marriage, I reached out to Sheila to work on Fight Like a Girl, a one-week activist training camp for racialized teens. It was a lot of fun; she worked with them to develop a brief and the youth just loved it. I learned a lot too, because I saw how important it was to actually hire service users and how much the youth enjoyed the challenge of being given the opportunity to actually execute the work.

TP: Something that we love doing is adapting community-led research projects to really lift up people’s already existing wisdom and skills. We’ve tried to create space for participants to express that they already have a lot to offer, instead of taking a more top-down approach, that often tells marginalized communities and youth that they’re starting from scratch and need to gain expertise from outside of their experience and communities.

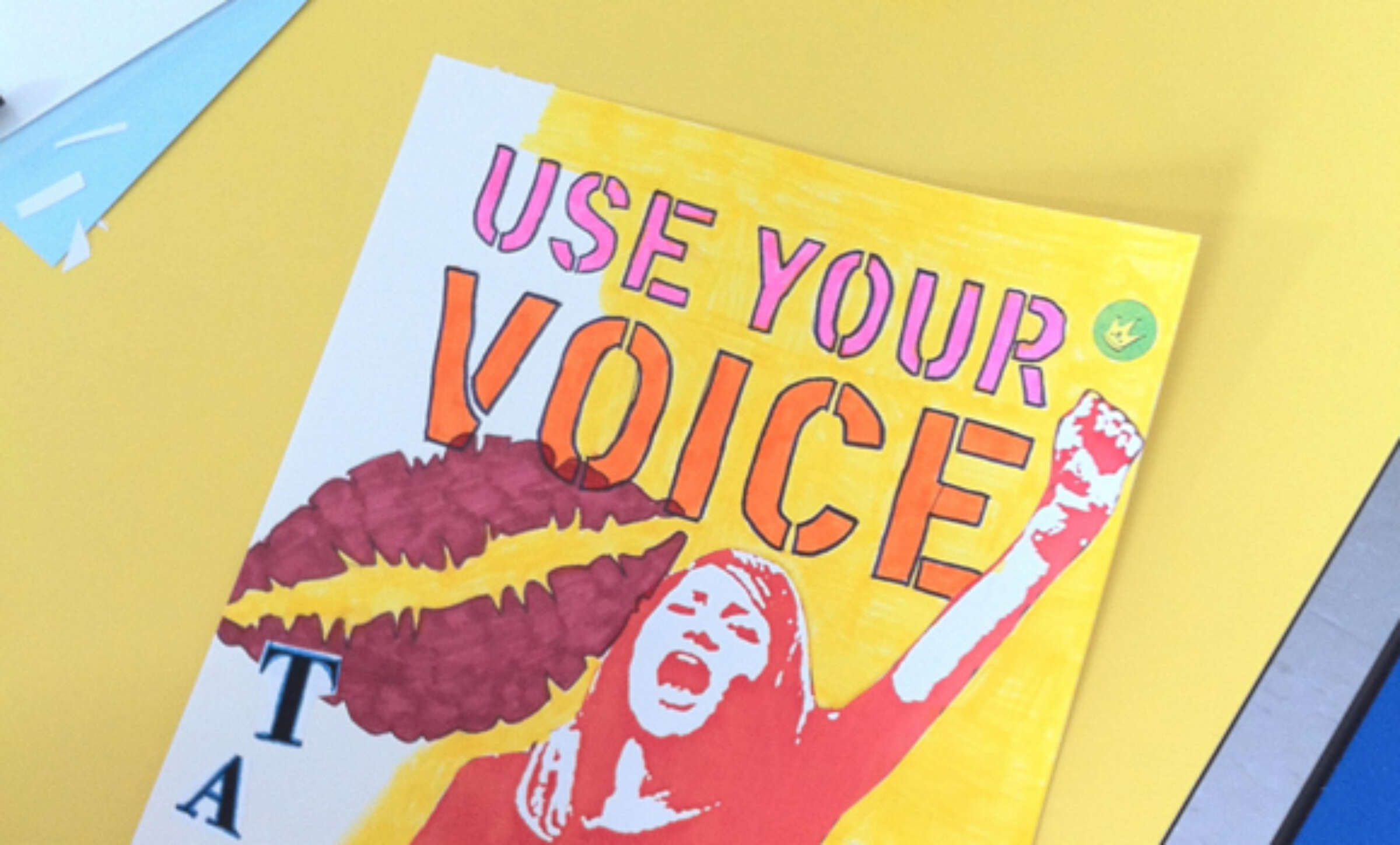

MR: Yes! I find that this is where I see the most innovative work actually happening. The thing that was really innovative and fun about the Fight Like a Girl programming that Sheila organized was that she brought in other artists to do a series of workshops. As a group, the young people decided on a theme and message, and then split into groups to make podcasts, zines, posters, spoken word pieces, or a social media outreach campaign.

Then with the award-winning Stop Elder Abuse project The Public later did, it was amazing, because it really gave the aunties a chance to talk about gendered violence and elder abuse in a much more systemic approach. It was intergenerational, with elders and youth really talking about systemic violence, and what the video and the PSAs could look like, and they each had the opportunity to speak their words in their mother tongue. I also think it was a great idea to include the outtakes at the end of the video. People loved that; I’ve shown this video all over the world. A couple years after we did that project, the European Union actually sent a delegation of MPs to Newcomer Women’s Services and they loved the video. I noticed that the MPs engaged with the women, the services users in a much more respectful and different way. They didn’t see them as downtrodden victims; they were actually really impressed with all that the elders were doing for themselves, each other, and their communities.

TP: A big part of that project that was really powerful was that there was this authenticity to it. It was really sincere and I think sometimes those things are positioned against each other. There can be a certain aesthetic people associate with a really “powerful” PSA, like making it catchy in these really specific ways and having to sort of shape or fit people into a certain mold.

It's really great to hear how you saw how people engaged with the work. When you worked at Newcomer Women’s Services, you saw a lot of the participants regularly. What are some ways that you noticed The Public’s programming change or impact your service users?

MR: At the time there were a lot of climate change refugees, it was very much in the media around people fleeing sub-Saharan Africa to go to Italy and Greece. I went up to the women afterwards and thanked them, because our women who were in that video really humanized the issue around the political and economic context that created the conflict that was forcing them to flee, which is very different from the narratives that we usually hear about refugees. I saw the impact that they had on a group of members of Parliament and the women felt really good standing in their own power. As the women were training and teaching the MPs, it was very much that they had allowed the MPs to go into their space rather than the other way around.

So think there’s a lot of power included in these tools, and the community members feel very comfortable in standing in their own power after they develop something like that. It’s something they can show their friends and family. In the video for the elder abuse, the woman who speaks at the very end, her hair is covered, she’s in her early nineties and every time I show that video people go “aww!” but it’s not just because of her being a nice granny. She’s a journalist back home and she had some very challenging circumstances in her life, but she was really proud that she was able to do journalism for that project.

I definitely think the way the women who were in the video engaged with the members of Parliament showed how personally dedicated they were to the project. I hadn’t asked any of the women to share their personal stories, but the women actually chose to share them. One of the women spoke to her experiences in Syria, and another from Liberia, and you know, all the MPs started crying. Our receptionist actually came out and asked “what did they say to them?”, because there were these men standing weeping in our hallway. But it was because the women felt like they needed to tell them their story in order to impact public policy. So I think the fact that that wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t had that communications process, developing the brief, made the project deeply impactful.

TP: It sounds like they really had built that sense of ownership over their power, their voice, and their truth.

MR: I still see and chat with them from time and time and absolutely, it gives people a sense of pride to have a platform to talk about political issues in a way that they may not in a standard ESL school or more traditional youth program. I think that what’s important about the power of media and art, is that it can be done in a way that allows people to self-reflect, but it’s trauma-informed, and it’s not triggering. So I’ll give you an example. We’re doing right now at YWCA some really amazing training around advocacy and activism, but a big piece of that is having people tell their personal stories. A lot of people misinterpret that as something where they have to speak to their trauma, but I think that what sets us and The Public apart is that we are not asking people to disclose their trauma. We are not further victimizing them, we are naming and honouring them as experts in their own lived experiences, and in the systems that impact them and their communities.

TP: Thank you for sharing your insights with us, Maya

Photo credit: Manette Ingenegeren and Teferi Mekonen

Date

How do you want to change the world and how can we help?

Let’s Connect